As I’m getting closer to a decision on where I’ll going to rabbinic school next fall, I find myself thinking about where I’ll be living. I’ll be in a new city for the fourth time in 8 years, back in the US after time in Kyiv, Barcelona, and Jerusalem.

There are so many things to establish when moving to a new place: routines, community, and importantly, a dwelling of some kind.

My nomadic spaces

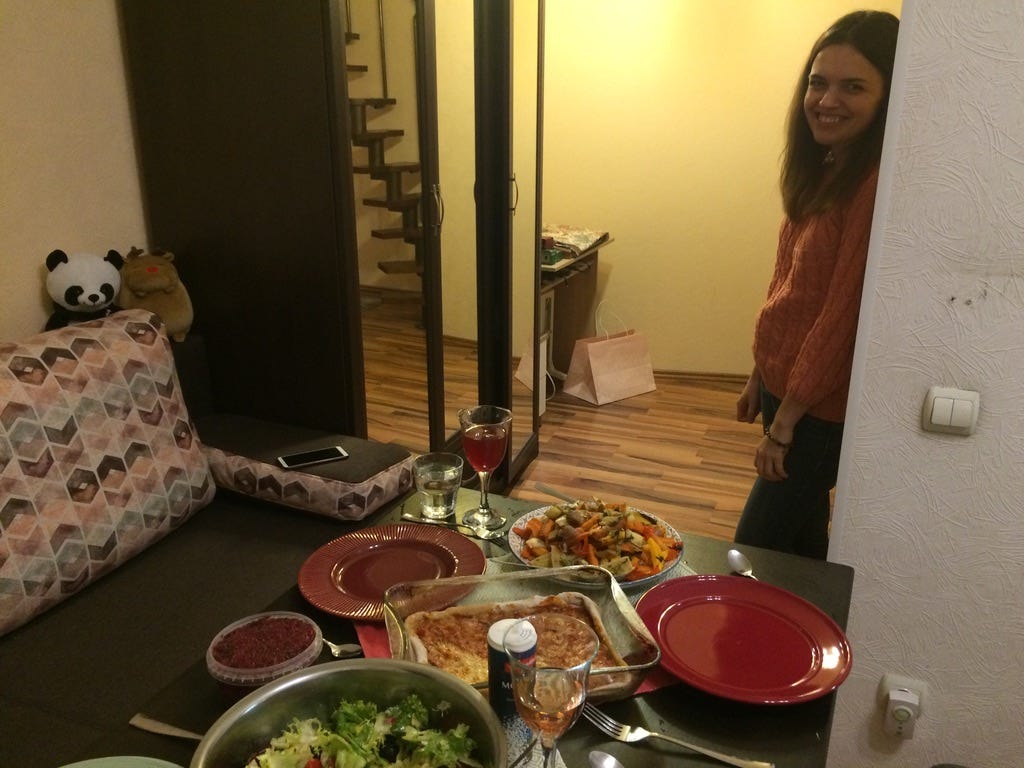

In Jerusalem, I’ve set up my apartment in a way that feels transitory: knowing that I’d likely only be here for a year, it didn’t make sense to put a lot of effort into getting furniture, or books, or the kind of cookware that I’d really enjoy using. After all, I knew I’d be leaving soon, and planned on traveling light, filling only the suitcase I came with. That was how I made my last moves, too, from Kyiv to Barcelona and Barcelona to Jerusalem.

Each time I moved, I had to carefully consider what was important enough to deserve space in the suitcase: the essential clothes, the favorite books, a few small pieces of art and objects that reminded me of special people and the time we shared, the gadgets and other practical things that I’d use most or find hardest to replace.

Each time, the choices about what to bring became more intentional, and so did my thinking about what new things to acquire. Before buying anything durable, I’d consider how much I really needed it, how important it would be to have it in my current location, and what I’d do with it when I left. Would it be useful or meaningful enough—and small enough—to carry with me? Would I be ok leaving it behind, perhaps leaving it with a friend, perhaps selling or donating it?

I’ve always been sensitive to the space around me, especially in the place I live. I like to form a connection to my dwelling by choosing a place with a lot of light, by bringing in beautiful objects that resonate with me, by rearranging and changing the furniture over and over until it feels just right. I like the space to feel special, sacred.

How much is enough? Building sacred space in the wilderness

In this week’s Torah portion, we read about the construction of the Mishkan, the sacred tent of meeting that the Israelites built and carried with them as they wandered in the wilderness.

After Moses has told the people about the Mishkan’s design, he invites them to donate the materials that would be needed for its construction: “Take from among you an offering to God—let everyone whose heart is willing bring an offering to God…” (Exodus 35:5)

The people bring gold, silver, and copper; cloth of blue, silver, and crimson; animal hides and acacia wood; oil for lighting and spices for incense; precious stones that the priest would wear during official duties.

Their generosity is such that the craftspeople report to Moses: “The people bring much more than enough for the service of the work, which God commanded to do.” (Ex. 36:5)

Moses tells the people to stop bringing materials: “Let neither man nor woman make more effort for the offering of the sanctuary.” (Ex. 36:6)

The people refrain from bringing more gifts.

Ramban comments on how remarkable this sequence of events was: the people are praiseworthy for the donations they brought; the craftspeople for their trustworthiness in reporting the excess; and Moses for his order to stop bringing materials.

It’s a sharp contrast to many communal building projects. It’s often a challenge to secure the resources needed to carry out the work. Even if the community brings more than is needed, how many leaders have the restraint to tell the people to stop bringing, instead of using what’s left over to add to the scope of the work, or holding onto it for the next project?

Seforno points this out: the building of the Mishkan was different from the Israelites’ later communal projects of constructing sacred spaces, the temples built under Solomon and Herod. God had given instructions about the work that was needed. The people, the craftspeople, and Moses respected those instructions.

There was more than enough to complete the work without fear of running out of materials. The temptation to gather or use more than necessary was avoided.

Why might the project have been carried out with such precision, with enough support so nothing had to be omitted, with enough restraint that nothing had to be added?

I’d suggest that it was because of the people’s situation as travelers in a desert.

Over the months since they left Egypt, the people had faced discomfort, shortages of water and food, and attacking enemies. They had spent a good deal of time packing and carrying their belongings as they moved between camps.

They might have learned how important it is to act together and support one another, especially in a region where the environment is unforgiving and resources are limited. They might have started to learn how to live with new kinds of constraints on their ability to acquire and move materials.

These kinds of learnings might have encouraged generosity. They might have also encouraged restraint. The balance, it seems, allowed them to build a sacred space, a sanctuary where God could “dwell among them.” (Ex. 25:8)

Longing for sacred space

I’ve been longing to create sacred space around me in a way that I haven’t done this year. When I recently told a teacher about this, she suggested that this kind of space could be built at many different scales.

As Moses and the Israelites knew, it’s not always the right time to build a great stone edifice. Sometimes a simple tent, constructed with care, can be a space that brings the sacred close.

Sometimes it can be even smaller: maybe not a whole shelf of books, just one or two important ones. Maybe not a full-scale painting, just a carefully chosen postcard tacked to the wall.

Although I’m already looking toward my next move, I’m excited to do something small to make the space where I am now feel more special. And I’m looking forward to putting intention into making my next dwelling a sacred one.

Shabbat shalom 🕊️ 🌍

Thanks for this post, Noah. It feels very relevant to us right now (and always!)!

Having moved cities I relate to what you wrote. Also love the idea that you can do it at different scales - can be a small corner or a room or a garden. do what works for you.